April 2022

Reconciling PPP Expiry with Net Zero Objectives

PPP Contract Expiry

The UK’s Infrastructure and Projects Authority (“IPA”) recently published their guidance for contracting authorities on Preparing for PFI Contract Expiry. The direction provides toolkits and recommendations for how public sector contracting authorities can approach the expiry of these contracts. The guidance also stresses the importance of stakeholders working together. This recognises that a PPP contract’s expiry interweaves with a separate workstream on the provision of future services.

In this context, there is an emphasis on handing back assets to support that future provision:

“At the point of contract expiry, the assets will typically be 20 to 30 years old. It is inevitable that the authority’s requirements, guidance (for example, Building Bulletins) and policy/legislation (for example, net zero carbon obligations) will have changed in this period. The authority should therefore review the hand back criteria to determine whether they align with future needs… the hand back requirements, and thus also the focus of lifecycle spend, may need to be reconsidered in order to reflect any changes to the authority’s needs.”

The impetus for defining and articulating these future needs will come from the Authority. The PPP Project Company can highlight opportunities for how expiry can facilitate the transition towards future needs (either within the existing contract or through variations). The default position for the PPP parties is to comply with the agreement unless instructed differently.

Changes from the existing provision will need the Authority to confirm priorities for the future use of the asset. Agreement and recording of any consequent adjustments to the expiry process and hand back become variations to support the transition.

Net Zero Carbon

One clear example of the challenges of reorienting an asset is reconciling contractual compliance on an expiring PPP contract. This ensures further progress towards Net Zero and embeds it into the future operation of the assets as it reverts to public sector control.

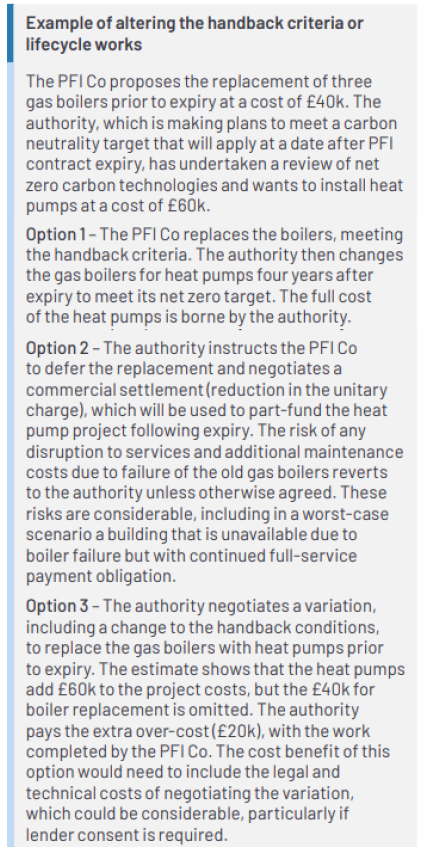

The IPA guidance uses an example, likely on many PPP projects, focusing on a PPP Project Company (“PPP Co”). That is planning the replacement of existing gas boilers to meet its contractual hand back obligations.

The contract is in writing long before the exploration of Net Zero. Against that contractual requirement, the IPA guidance gives an example of an authority that has made a net zero commitment. As part of that commitment, the authority has a strategy to install heat pumps in place of gas boilers. Although the heat pumps are more expensive, they have a much lower operational carbon output.

Our Research Shows…

A recent Vercity feasibility study supports that view. We identified that for a representative three boiler school, replacing with ground-source heat pumps for heating (while retaining gas for hot water) could have the following impacts:

- 77% Reduction in gas consumption per annum (360,000 kWh to 80,000 kWh), with a corresponding decrease of 57 Tonnes CO2eq.

- 40% Increased electricity usage per annum (130,000 kWh to 182,000 kWh), with a corresponding rise of 11 Tonnes CO2eq.

- A net 36% decrease in whole site carbon dioxide emissions tonnes per annum.

For the original site emissions that remain, there is a change in classification for the majority from Scope 1 (for boiler gas) to Scope 2 (for heat pump electric). The difference in Scope classification could link with the procurement of certified zero-carbon electricity, eliminating those Scope 2 emissions entirely.

The IPA guidance below identifies three options in this scenario:

Driven by the requirement to comply with the contract, Option 1 will be the default position.

Option 2 would need the authority to indemnify the PPP Co against any failure of the boilers. That could present an operational risk that many contracting Authorities find unacceptable. If the boilers fail (increasingly likely if life-expired,) there would be no contractual deductions, and the authority would fund replacements.

This option would also defer the realisation of the environmental benefits of carbon reduction.

Option 3 enhances the contractual baseline and the authority only contributes to the enhancement. The IPA correctly identifies that legal and technical costs are of consideration, alongside the practical implications. These include whether the heat pumps fit with the location of current boilers, a factor that could impact the cost.

There may be grant funding available calculated against the total impact of the upgrade to heat pumps, not just the authority funded proportion.

The third scenario should be optimal, and if the variation takes place after the repaying of debt, there will be no requirement for lender consent.

Early discussion on potential replacement and timing of any variation will need the PPP Co and the Authority. Working together on the timing of a replacement and how best to unlock available grant funding.

To maximise the impact and benefits, other measures may also be up for consideration. These include converting water heating and/or installation of solar panels. However, appraisal of these will need specialist input. The Authority could benefit from assessing this while the PPP consortium and its expertise are in place rather than waiting until after the contract expiry.

Why wait until expiry?

The example outlined by the IPA guidance is not only relevant for those projects approaching expiry. It could now be adopted pro-actively by understanding when boilers are programmed for lifecycle replacement and varying the criteria. Depending on the availability of grant funding, it may be possible to meet some or all of the additional cost, while spreading future replacements (the £20k from the example) over several years as additional unitary payment rather than being found as a single lump sum.

The use of water to water heat pumps on a wide scale retrofit solution serving an existing hydronic heating system remains a relatively new technology. Therefore, it is unlikely to yield any material maintenance savings and this is not to be expected. However, that should not detract from the potentially significant carbon reduction impacts.

Using the example, but for a project that still has 15 years until expiry, deferring a decision could lead to the emission of a further 555 tonnes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

Complex Projects

For multi-stakeholder projects such as PPP, enhancing a contractual baseline is likely to be the most realistic and cost-effective route to achieving Net Zero objectives. This also ensures that the positioning of assets is complete with their future purpose in mind. In addition, implementing these enhancements while there is an existing and established consortium managing the asset brings the expertise to bear. It will ensure any initial operational issues or snagging can be ironed out.

Effective collaboration between parties allows for these replacement decisions to be mutually beneficial. Doing so means that the owner may benefit from their emission reductions and potentially more efficient equipment. A plan that may require lower maintenance or have longer equipment life.

Vercity has demonstrable experience in ensuring continuity of service to critical social infrastructure during transition periods. In addition, we have a track record of managing contracts before and after the point of expiry, and of delivering infrastructure contributions toward net zero targets.

- Preparing for Net Zero: Mark Cade ([email protected])

- Asset Innovation: Dan Earnshaw ([email protected])

- PPP Contract Expiry: Patrick Hamill ([email protected])

Related Articles